Martha note: I wrote the following book story for npr.org. It was posted yesterday. FYI: In my opinion, on this National Read Aloud Day, the Oracle of Stamboul would be an absolutely fabulous book to read aloud to a child -- or a partner! (buying through highlighted link benefits WMRA through our Amazon partnership!)

Getting paid to write your first novel is as rare as getting paid to sing in the shower, so first novel writers often have to hustle creatively for their keep. Take, for example, the financial adventures of Michael David Lukas (Brown undergrad, MFA from Maryland), who just published novel No. 1.

The Oracle of

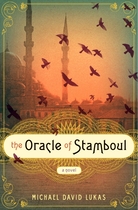

Eleonora was conceived in Istanbul, Lukas explains, when he wandered into "a narrow dusty little store. In the back was a crystal bowl, and in it was a picture of this little girl with the most self-possessed, wise look in her eye. When we made eye contact, I knew that this was my protagonist and that my novel would be set in Istanbul."

Michael David Lukas generally goes by all three of his names because he doesn't want to be confused any longer with Michael Lucas, who is a hugely popular gay porn star.

"I would Google myself," Lukas says, "and he would pop up first, even though our names are spelled differently. I couldn't get away from him."

Lukas subsequently blogged for the Virginia Quarterly Review, writing that "a triumvirate of names gives the author a certain unassailability and gravitas."

The Oracle of Stamboul

By Michael David Lukas

Hardcover, 304 pages

Harper

List Price: $24.99

Read An Excerpt

Perhaps, but I'd characterize Lukas more as someone who hovers lovingly over a story, whispering, "Enjoy!"

The Oracle of Stamboul begins this way:

Eleonora Cohen came into this world on a Thursday, late in the summer of 1877. Those who rose early that morning would recall noticing a flock of purple-and-white hoopoes circling above the harbor, looping and darting about as if in an attempt to mend a tear in the firmament.

I told myself that I would rather be a person who tried to write a novel and failed than be someone who abandoned their novel.

What have hoopoes to do with Eleonora? One wants to read on and find out — which is, after all, the job of a first sentence. Lukas says he "agonized" over that sentence — indeed over the perfecting of Oracle's first paragraph — for days, as well as over other narrative bits.

"It's gratifying," he says, "because those seem to be the same passages people respond to. But it's not a lesson I want to fully incorporate, because then I'll never finish the next book."

Courtesy Michael David Lukas

Lukas' novel was inspired by this photograph of a girl he found in a dusty shop in Istanbul.

He almost didn't finish this one. Oracle took Lukas the Biblical seven lean years to write, during which he lived from fellowship to grant to whatever jobs left time to write. In Oracle's"acknowledgments," the author thanks 10 literary foundations and organizations for financial support, among them the National Endowment for the Arts, the Ludwig Vogelstein Foundation and the Elizabeth George Foundation.

Halfway through, Lukas says, he "ended up having a crisis of the lean years and [starting] a career in socially responsible business." This, he discovered, while fine for others, was not fine for him. "During that time, I learned how hard it is for me not to write — and how hard it is to write with a full-time job."

So, it was back to full-time writing, funded by whomever Lukas could shake support out of and whatever paying work fit into the corners of his writing days. "I was asking people for money essentially all the time," he says. "I'm really, really thankful for all those people who work at organizations and foundations that give money and support to writers."

Lukas joined the long queue of first-time novelists who discover they keep going because, well, they have to.

"I knew I wanted to write this book," he says, "and I knew it would take a long time. But I didn't truly realize what that meant until I was years into the process and all my friends had graduated law school and were making 200 grand a year. Then I tried the socially responsible business thing and realized I would just have to double down and keep going. I told myself that I would rather be a person who tried to write a novel and failed than be someone who abandoned their novel."

Excerpt: 'The Oracle Of Stamboul'

The Oracle of Stamboul by Micahel David Lukas

The Oracle of Stamboul

By Michael David Lukas

Hardcover, 304 pages

Harper

List Price: $24.99

Eleonora Cohen came into this world on a Thursday, late in the summer of 1877. Those who rose early that morning would recall noticing a flock of purple-and-white hoopoes circling above the harbor, looping and darting about as if in an attempt to mend a tear in the firmament. Whether or not they were successful, the birds eventually slowed their swoop and settled in around the city, on the steps of the courthouse, the red tile roof of the Constanta Hotel, and the bell tower atop St. Basil's Academy. They roosted in the lantern room of the lighthouse, the octagonal stone minaret of the mosque, and the forward deck of a steamer coughing puffs of smoke into an otherwise clear horizon. Hoopoes coated the town like frosting, piped in along the rain gutters of the governor's mansion and slathered on the gilt dome of the Orthodox church. In the trees around Yakob and Leah Cohen's house the flock seemed especially excited, chattering, flapping their wings, and hopping from branch to branch like a crowd of peasants lining the streets of the capital for an imperial parade. The hoopoes would probably have been regarded as an auspicious sign, were it not for the unfortunate events that coincided with Eleonora's birth.

Early that morning, the Third Division of Tsar Alexander II's Royal Cavalry rode in from the north and assembled on a hilltop overlooking the town square: 612 men, 537 horses, three cannons, two dozen dull gray canvas tents, a field kitchen, and the yellow-and-black-striped standard of the tsar. They had been riding for the better part of a fortnight with reduced rations and little rest, through Kiliya, Tulcea, and Babadag, the blueberry marshlands of the Danube Delta, and vast wheat fields left fallow since winter. Their ultimate objective was Pleven, a trading post in the bosom of the Danubian Plain where General Osman Pasha and seven thousand Ottoman troops were attempting to make a stand. It would be an important battle, perhaps even a turning point in the war, but Pleven was still ten days off and the men of the Third Division were restless.

Laid out below them like a feast, Constanta had been left almost entirely without defenses. Not more than a dozen meters from the edge of the hilltop lay the rubble of an ancient Roman wall. In centuries past, these dull, rose-colored stones had protected the city from wild boars, bandits, and the Thracian barbarians who periodically attempted to raid the port. Rebuilt twice by Rome and once again by the Byzantines, the wall was in complete disrepair when the Ottomans arrived in Constanta at the end of the fifteenth century. And so it was left to crumble, its better stones carted off to build roads, palaces, and other walls around other, more strategic cities. Had anyone thought to restore the wall, it might have shielded the city from the brutality of the Third Division, but in its current state it was little more than a stumbling block.

All that morning and late into the afternoon, the men of the Third Division rode rampant through the streets of Constanta, breaking shop windows, terrorizing stray dogs, and pulling down whatever statues they could find. They torched the governor's mansion, ransacked the courthouse, and shattered the stained glass above the entrance to St. Basil's Academy. The goldsmith's was gutted, the cobbler's picked clean, and the dry goods store strewn with broken eggs and tea. They shattered the front window of Yakob Cohen's carpet shop and punched holes in the wall with their bayonets. Apart from the Orthodox church, which at the end of the day stood untouched, as if God himself had protected it, the library was the only municipal building that survived the Third Division unscathed. Not because of any special regard for knowledge. The survival of Constanta's library was due entirely to the bravery of its keeper. While the rest of the townspeople cowered under their beds or huddled together in basements and closets, the librarian stood boldly on the front steps of his domain, holding a battered copy of Eugene Onegin above his head like a talisman. Although they were almost exclusively illiterate, the men of the Third Division could recognize the shape of their native Cyrillic and that, apparently, was enough for them to spare the building.

Meanwhile, in a small gray stone house near the top of East Hill, Leah Cohen was heavy in the throes of labor. . . .

Excerpted from The Oracle of Stamboul by Michael David Lukas. Copyright 2011 by Michael David Lukas. Published by Harpers. All rights reserved.

Excerpted from The Oracle of Stamboul by Michael David Lukas. Copyright 2011 by Michael David Lukas. Published by Harpers. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment